Historically, when the S&P 500 has fallen 10% and the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond has declined 50+ basis points, the U.S. economy has been heading into recession about 70% of the time. We reached both milestones in March. The economically sensitive small-cap Russell 2000 index is down 17% since last November, and Canada’s resource and financial-centric TSX is down 6% since December 6, 2024.

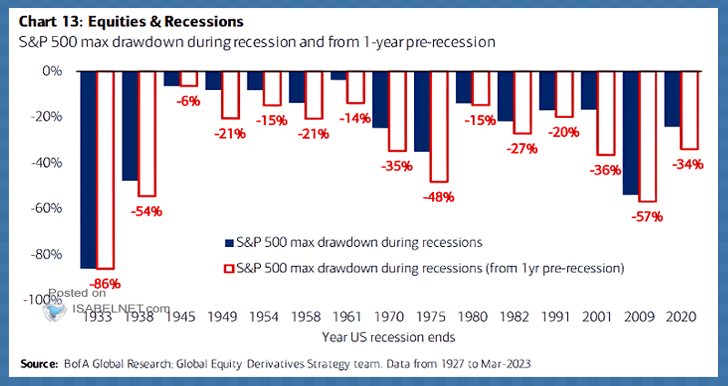

It’s worth noting that the average stock market decline during past recessions has been 30%, and 34 to 86% when valuations begin from extreme highs, as in 1929, 1973, 1999, 2007, 2020 (below) and now.

While official unemployment rates are still not far above cycle lows, credit delinquency rates (90+ days late) are already near their highest levels in 20 years.

The recent University of Michigan Sentiment Survey registered the greatest level of pessimism on personal finances ever recorded–worse than 2008. Just let that settle in a minute.

Knock-on risks intensify with age. As of early 2024, individuals 55+ held approximately 80% of all stocks, a significant increase from 60% two decades ago.

Everyone hates to see their portfolios decline, but capital loss later in life is harder to recover emotionally, psychologically, and financially. Losses while needing to withdraw for living expenses can severely reduce the longevity of savings and the likelihood that portfolios never fully recover — a scenario known as sequence of return risk. Outliving one’s savings remains among the top retirement fears.

As the economy and employment contract from here, central banks will continue easing efforts, but inflationary fears around tariffs may slow the pace and degree, at least in the near term.

For those who hope coming cuts are bullish for risk assets, it bears noting that the bulk of price declines have always come while the Fed is easing, not before.